|

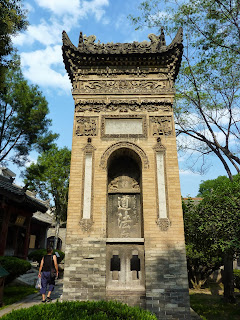

| First sightings - Xiaoyan pagoda. Built around 710 AD. |

The Little Wild Goose Pagoda isn't small by any means: the

'little' is relative. Unlike its larger

brother, this pagoda stands in a much more natural setting amidst a sprawling

garden. No granite and fountains here,

only shady paths, trees and plenty of birdsong.

It was a haven amidst the bustle of the city and we just sat, stretched

our legs and relaxed.

|

| In 1487, the 15-storey pagoda was split by an earthquake/ Appears that it was glued together in the '60s. |

Early portraits

Next door was a small lake with a more manicured

garden. Geese strutted around waiting to

be fed. Dustbins dotted the garden

expanse and they were being used. There

was very little litter, something that struck us again and again in China. Better civic sense? The threat of fines? More efficient cleanup? Convenient dustbins? All of the above? Whatever it was, it seemed to work. Even the most crowded places we visited were much

cleaner than their Indian counterparts.

The Xian museum did not rate any special mention in the

guidebooks. We wandered in for a quick

look-see and some air-conditioning (entry was free!). We ended up spending the better part of an

hour walking around. Apart from the model

of tenth century Xian, there were exhibits of items excavated from the vicinity

going back some 3000 years. A profusion

of Buddhist relics from the Tang dynasty accompanied remnants of pottery,

building materials and other artifacts unearthed as the foundations were laid

for today's Xian. As with other museums

we visited in China, everything was neatly laid out and labeled. Sadly, the contrast with Indian museums was

only too evident.

|

| Gilded Bodhisattva from the Tang period |

|

| "Gold traced and painted statue of Avalokiteswara". Northern Zhou dynasty |

|

| A stele with Buddhas on all four sides - from the 4th century |

|

| The little lake beside the museum |

| ||||

| The pagoda, with modern Xi'an behind |

We were making our way out of the grounds and almost missed

the small building off to one side.

Exhibition on the Cultural Revolution, said a banner. My wife's curiosity overcame my reluctance and

we went in to take a look. The exhibits

- photographs, a few articles and commentary (in English!) - occupied the

corner of a room. The unequivocal

message was this: Chairman Mao was a great man who unified the country and

helped drive out the Japanese, but his Cultural Revolution was a big

mistake.

Reformers led by Deng Xiaoping

learned from the social and economic chaos caused by the Revolution and

initiated the reforms that set China on the path to growth and prosperity. So there it was in black and white: official

acknowledgement that Mao had erred, that Maoism had outlived its usefulness,

and that it was time to move on. Perhaps

we need to send Indian Maoists and Marxists to China for some re-education.

Apart from his ubiquitous presence on currency notes and his

portrait and mausoleum in Tiananmen Square, Mao was absent in China. There was plenty of history and culture being

resurrected and burnished wherever we went. It appeared to me, though, that the nominally

communist ruling party was gradually airbrushing its communist past out of its

history.

|

| The drum tower |

Old Chinese cities marked the beginning and end of the day

with the chiming of bells and the beating of drums. (Earlier still, battles were fought only at

specified times, and the bells and drums marked the beginning and end of each

day's battle: the custom survived the era of wars.) The well preserved (or well restored) Bell

Tower of Xian sits at the heart of the walled city, encircled by a never-ending

stream of traffic and surrounded by monumental Soviet style buildings dating

from the 1950s. A short distance away,

adjacent to buildings housing McDonalds, Starbucks and Haagen Dazs outlets,

sits the (equally well preserved/restored) Drum Tower. These are large, impressive, structures and

hold their own even in their twenty first century surroundings.

Exploring the Muslim Quarter Walk a little further, turn right past a large

mall, and you find yourself in a narrow alleyway, dodging scooters and

motorized rickshaws. This is the Muslim

Quarter of Xian, another remnant of the time when the city was the terminus of

the silk route. The looks and sounds of

the modern city are completely absent here.

We felt we were in some Middle Eastern bazaar. Shops and restaurants spilt out onto the

street. Mounds of dried fruits and dates

filled open sacks. Skewered kababs

awaited their turn in the oven, as did circles of unleavened bread.

Walk a little further, turn right past a large

mall, and you find yourself in a narrow alleyway, dodging scooters and

motorized rickshaws. This is the Muslim

Quarter of Xian, another remnant of the time when the city was the terminus of

the silk route. The looks and sounds of

the modern city are completely absent here.

We felt we were in some Middle Eastern bazaar. Shops and restaurants spilt out onto the

street. Mounds of dried fruits and dates

filled open sacks. Skewered kababs

awaited their turn in the oven, as did circles of unleavened bread.

The obsessive tidiness of the main thoroughfares was absent

here. The Chinese street signs were the

only indication of where we actually were.

The alleyway was too narrow for traffic, but that didn't stop the laden

scooters and rickshaws attempting to make their way through the pedestrian

crowds.

We came to a junction and turned into another crowded

alleyway moving, we hoped, towards the Great Mosque. There was no sign of any large mosque (or any

large structure) anywhere. More of the

same shops, passageways leading to small habitations, bicycles and scooters,

the odd tree, but no mosque. We looked

at our map. It had to be here somewhere,

except that there was absolutely nothing anywhere resembling a large green

space with a mosque. We finally stopped

and asked for directions. Sign language

and much pointing at the map, in case you were wondering. As in the rest of Xian, English is limited to

the road signs.

We were pointed down an even narrower covered alley, its

shops filled with tourist bric-a-brac. T-shirts

featuring Obama and Mao, playing cards with Saddam Hussein's smiling face, the

Little Red Book translated into the most unexpected languages, mugs, mats,

scarves and much else. There was none of

the competitive hustle and bustle of a true middle-eastern bazaar. Negotiations were civilized. If we only wanted to look, no one bothered

us.

We then came to a gate with a polite gentleman wanting to know where we were from. He seemed pleased to hear that we were from India. And, quite unexpectedly, there we were, in the first (of three) courtyard of the Great Mosque.

The mosque dates from the eight century, but as with

everything else in China, it is difficult to tell what has been restored, added

or repaired or whether even any part of the original structure still survives. That apart, this is a mosque like no

other. This is very Chinese set of

buildings and even what passes for a minaret is a Chinese tower. Arabic calligraphy here and there is the only

indication of its purpose.

It was quiet and restful inside, with plenty of trees

providing shade. The sounds of the

bazaar and the larger city are absent.

The chatter of birds and the distant sound of prayer were the only

sounds.

I couldn't help thinking that this place was a kind of

terminus. Islam came this far but,

running up against more ancient beliefs, didn't go any further. These buildings with their syncretism of

Chinese styles and Islamic calligraphy marked an outpost. Today, we are told, there are only about

20,000 Muslims in Xian. Judging from the

white caps and headscarves we saw near the mosque and their absence elsewhere

in the city, it looks as though most of them live and do business in this

crowded jumble of streets.

It was past six, the sunlight slowly softening and painting the Bell Tower in mellow hues. Across, in a large 1950s era edifice, was the post office. We wanted to send a few postcards and wondered if we were too late. We needn't have worried. As elsewhere, pragmatism ruled. There were others sending parcels, posting letters and sticking stamps on postcards. People needed to use the post office at this hour, and it was open as a result. No protests in the People's Republic about long working hours. (Interestingly, the postcards we sent to the US reached in a week. The postcards to India took three months. I wonder why.)

|

| The Xi'an People's Hotel - a communist relic, now under renovation in private hands |

To be sure, life is far from perfect in China, but by and

large there is a sense that the government's job is to do something for its

citizens. We walked back to our hotel

along broad, tree-lined sidewalks, and couldn't help thinking that this small

pleasure, a quiet evening stroll, was impossible in our native Chennai.